Introduction

The article that follows provided the basis for a talk by Professor Maddie Gray in 2023

The parish church at Llantrithyd in the Vale of Glamorgan holds a remarkable collection of post-Reformation ledger stones. Many explicitly request prayers for the souls of the deceased, particularly children, from the prominent Mansell and Aubrey families. These memorials challenge conventional narratives of the Welsh Reformation, revealing a deep-rooted conservatism blended with loyalty to the Tudor state.

Overview

- Llantrithyd church contains a unique set of late 16th-century ledgerstones with prayers for the dead, especially children.

- These requests for intercessory prayer contradict Protestant doctrine, yet there's no evidence of open recusancy.

- The Welsh Reformation was marked by religious conservatism and political loyalty.

- Cross slabs and traditional iconography persisted in southeast Wales longer than elsewhere in Britain.

- The emotional grief of losing children appears to have driven some families to defy doctrinal changes.

- These memorials offer insight into a nuanced, pragmatic religious identity during a time of confessional change.

Pray for my child: the Mansell and Aubrey ledgerstone memorials at Llantrithyd.

Abstract

The parish church of Llantrithyd in the Vale of Glamorgan has several late sixteenth-century cross slabs, four of them asking for prayer for the souls of children from the leading local landowning family, the Mansell/Aubrey family of Llantrithyd House. While post-Reformation cross slabs are surprisingly common in south-east Wales, such an explicit request for prayer is unusual. However, there is nothing to suggest that the Mansells and Aubreys were ever overtly recusant Catholics. These slabs are an extreme example of the combination of traditionalism and loyalism which characterised the Welsh response to the Reformation.

The parish church at Llantrithyd is justly famous for its three-generation monument to the Bassett and Mansell families. John Newman praises it for the way its "multi-coloured splendour cascades down at one's feet at the entrance to the chancel." Llantriddyd also has a rather endearing effigy monument to a late thirteenth-century civilian, his corkscrew curls looking like they were moulded in Plasticine rather than carved out of Sutton stone.

The church was known to have cross slabs in the sanctuary, often assumed to have been medieval. When the church was restored in 1897, the architect acknowledged that he was "not at liberty to disturb in any way" the "ancient memorial stone slabs" covering the chancel floor.

In his survey of the medieval churches of the Vale of Glamorgan, Geoffrey Orrin mentioned "several incised sepulchral slabs" though the only detail was of "one with a Calvary cross bearing the date 1586" (the monument to John [William] Bassett described below).

Until recently, it was impossible to inspect any of these slabs as they were covered by carpet and the decking for the choir stalls. The sanctuary carpet has now been removed in preparation for restoration work on the triple-decker monument, revealing not medieval cross slabs but a remarkable collection of late sixteenth-century ledger stones to other members of the Bassett, Mansell, and Aubrey families. Taken together, they throw new and surprising light on the response of the local élite to the great religious changes of the sixteenth century.

The Reformation in Wales: Tradition and Change

The Reformation is still one of the most bewildering issues of Welsh history. There is little or no evidence of discontent with what the Catholic Church had to offer in the early sixteenth century: traditional bardic poetry, wills, and church buildings suggest enthusiasm for the beautifying of churches, devotion to the saints, and a desire for intercessory prayer for the souls of the dead.

However, there is similarly little evidence for resistance to religious change in the sixteenth century. Wales has traditionally been regarded as a heartland of recusancy, second only to Lancashire, though openly recusant Catholics were always a very small proportion of the population. Kate Olson has certainly teased out a number of examples of low-level and passive resistance. Still, there was no Pilgrimage of Grace or Prayer book Rebellion, even though for most people, the 1549 Book of Common Prayer was in a foreign language and lacked familiarity with the traditional Latin liturgy.

In this, Wales contrasts with Ireland, where open adherence to the Catholic faith led to harsh repression. Comparing the Welsh and Irish experiences, Ciaran Brady and Brendan Bradshaw assumed that the Reformation in Wales was accomplished, if not with ease, without resistance.

Aftermath and Adaptation

As England settled into the Elizabethan compromise, the people of Wales were generally regarded as traditionalists and even backsliders. However, reports from the period indicate a general outward conformity, with little open disobedience or resistance, though complaints about lingering traditional practices were common among bishops.

Traditional funeral customs, including bells, candles, communal casting of earth on the corpse, and even prayers for the dead, remained widespread.

Cross Slabs and Ledgerstones: Symbols of Conservatism

Cross slabs in England are extremely rare after the Reformation and are frequently assumed to commemorate Catholics. However, in southeast Wales, post-Reformation crosses are common, with about 160 identified in churches across Glamorgan, Monmouthshire, and south Breconshire.

Some cross slabs did commemorate known Catholics, but others were clearly commissioned by loyal members of the established church, including clergy.

The Llantriddyd Ledgerstones

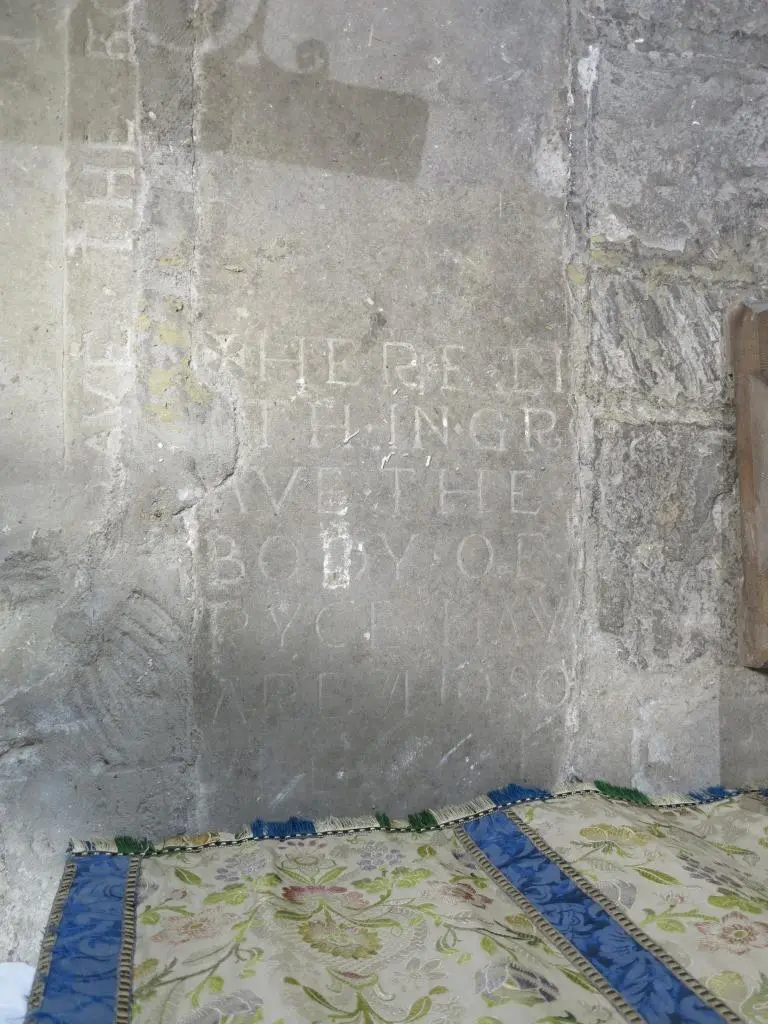

The ledgerstones in the sanctuary at Llantrithyd offer evidence of an even more determined conservatism. Most have crosses in a distinctive style, with short, heavy, splayed arms, a tapering shaft, and a three-stepped base with clearly defined steps. The border inscriptions are in generally well-formed square Roman capitals, with some reversed letters and spacing issues.

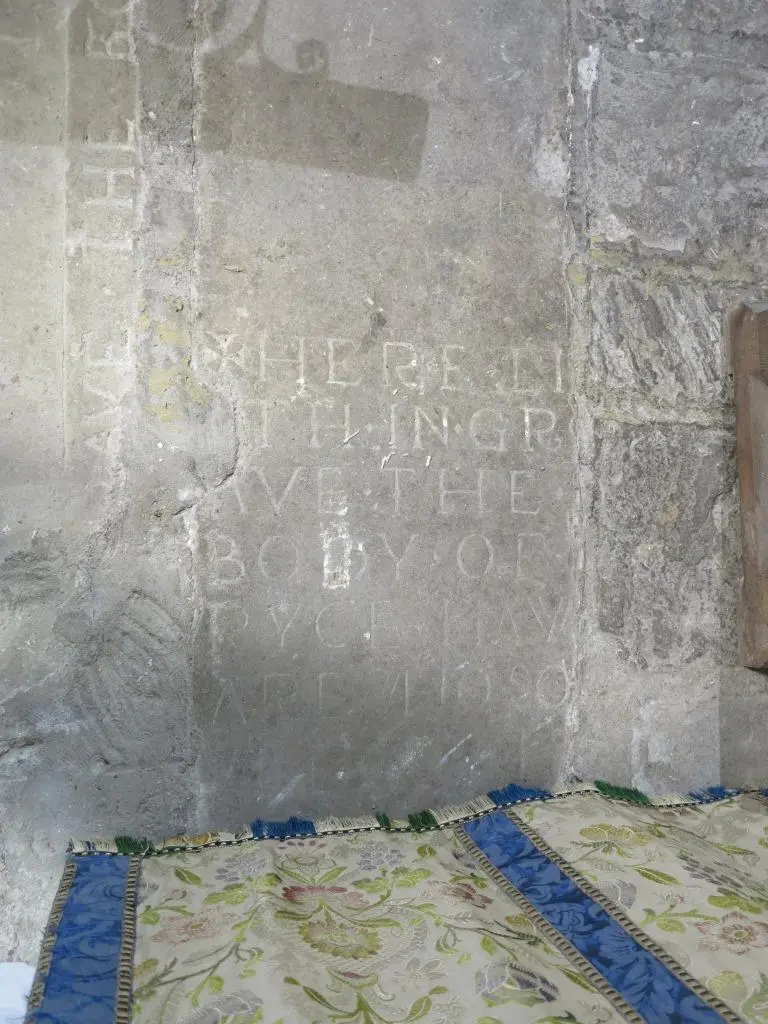

Virtually all of them commemorate members of the Bassett, Mansell and Aubrey family, though there is one to a Rice Haward, possibly a family employee. Significantly, four actually have inscriptions asking for prayer for the souls of the dead, in clear defiance of reformed thinking.

Notable Examples

- Ryce Mansell (d. 1583): The inscription reads:

PRAY - FOR - THE - SOULE - OF - RYCE - MANSELL - HERE - IN - GRAVE - AETAT ... ANNO - DOMINI - 1583.

Rice or Rhys was the son of Elizabeth Bassett and Anthony Mansell. He predeceased his parents. - Blanche Aubrey (d. 1588):

PRAY - FOR - THE - SOULE - OF - BLANCHE - AUBREY - HERIN - GRAVE

Blanche was the baby daughter of Thomas Aubrey and Mary Mansell. - Willeford Aubrey (d. 1594):

The inscription is barely legible but was recorded as:PRAY FOR THE SOUL OF WILLEFORD AUBREY 1594.

Parish registers confirm her burial as a young child. - A third miniature cross slab (d. 1573):

The inscription is now illegible but was recorded as:PRAY FOR THE SOUL ... 1573.

Likely commemorates Edward and/or William Mansell, both of whom died that year.

Prayer for the Dead: Doctrine and Practice

Prayer for the dead was a defining issue of the Reformation. The late medieval doctrine of Purgatory and the idea that the prayers of the living could relieve the sufferings of the dead were central to Catholicism. The Reformation unravelled this structure, but in Wales, the transition was more gradual and less confrontational.

Virtually all the surviving Glamorgan wills for the period up to 1536 contain bequests for prayer for the testator's soul, though these provisions were less elaborate than those in English wills.

Grief, Childhood, and Memorialisation

It may be significant that the four monuments which most clearly ask for prayer are those to children. While it has often been assumed that people in the past did not identify emotionally with their young children, studies of poetry and memorials suggest otherwise. The Llantriddyd memorials can be read as expressions of overwhelming parental grief and a determination to commemorate children in a way that defied the instructions of the state church.

- Blanche Aubrey was likely less than a year old at her death.

- The willingness of parents to make such public and challenging requests, defying church teaching, suggests the depth of their grief.

Catholicism, Loyalty, and Identity

But were the parents of these Mansell and Aubrey children Catholics? The answer depends on the definition of "Catholic." The evidence suggests that while the families were deeply traditional in their beliefs and practices, they were loyal to the Tudor state and outwardly conformed to the established church. There is no evidence that they were openly recusant after 1558.

The Llantriddyd tombs are unique in South Wales because they explicitly request prayer for the deceased after the Reformation. Other tombs in the region display crosses or the IHS trigram, but explicit Catholic formulae are rare.

Conclusion

The Llantrithyd tomb slabs are a striking example of the distinctive Welsh combination of traditionalism and loyalism—the same traditionalism that bishops deplored but which the Queen and the Privy Council did not see as a threat. These monuments reflect a complex interplay of faith, grief, loyalty, and local identity in post-Reformation Wales.

This article originated from a visit to Llantrithyd to examine the medieval effigy tomb there. Thanks to the parishioners for their care of the church and its monuments, and to the readers of earlier drafts for their suggestions.